Does psychedelic ‘medicine’ always give you what you need?

This is a post from the Ecstatic Integration Substack. To sign up for all our weekly posts, go here

The truth about drugs, When I was 18, I took LSD at a rave, and had a bad trip. I felt irrationally afraid and self-conscious for hours, and went to bed feeling I had permanently damaged my brain. Over the next few weeks, I felt paranoid, panicky and socially anxious. These symptoms faded but came back a few months later, and lasted for years. I was eventually diagnosed with social anxiety and PTSD. It took me five years to stop having panic attacks, a decade to regain my social confidence, and over 20 years for me to be capable of having a long-term relationship. The truth about drugs

Was that trip ‘bad’? Yes, it robbed me of confidence, scrambled my nervous system, changed my personality and made my life a lot harder. Do I wish it had never happened? That’s a trickier question. I suspect my life would have been much easier if I had never taken psychedelics. But that adverse experience also had positive impacts. I became interested in mental health, philosophy, spirituality. I experienced ‘post-traumatic growth’, eventually.

And this is the tricky thing about defining ‘bad trips’ — how I labelled that past experience affected my life in the present. When I believed ‘I have permanently damaged my brain’, that became a self-fulfilling prophecy. When I decided it was my catastrophizing beliefs in the present that caused my suffering and I found a more constructive frame for the past, I started to heal. The truth about drugs

Today I lead one of the first research projects on extended post-trip difficulties, what they’re like and what helps people who have them. I hope our work can help people in similar situations to the one I found myself at 18. We’re at an exciting moment when several psychedelic drugs are set to become legalized, whether for recreational, spiritual or therapeutic use, and millions of people could try them. Almost one in five British people are currently on anti-depressants, so the potential market for psychedelic therapy is huge. But how risky are psychedelics? What should people know before taking them? These basic questions are still being debated.

The least risky drugs out there?

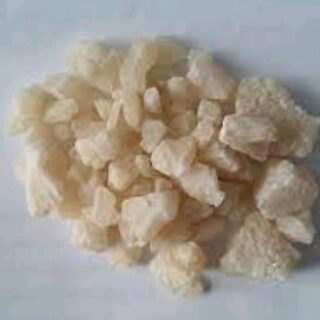

In debates over the risk of drugs, the table shown above is often produced. Alcohol is by far the most harmful drug, while magic mushrooms apparently have barely any risks at all. That table was published by Professor David Nutt in 2010, a year after he was fired as the British government’s ‘drugs tsar’ for saying LSD and ecstasy were less risky than alcohol. Nutt is one of the most powerful psychiatrists in the UK, and the graph has been hugely influential — I’ve seen it tweeted twice in the last two days, it’s often used as evidence in the decriminalization hearings now taking place in cities and states around the US, and it’s the graph that persuaded Christian Angermayer to try magic mushrooms and then become the biggest investor in psychedelics. Psychedelics are, according to Nutt, ‘among the safest drugs we know of’.

Nutt’s organization, Drug Science (‘the truth about drugs…free from political or commercial influence’ is its tag-line) recently played a key role in persuading Australia to legalize psychedelic therapy. Nutt was flown over by Mind Medicine Australia to give a series of talks, in which he told audiences that there has never been a psychotic reaction to psychedelics among the thousands of people who have been through psychedelic trials. He also told Australian media that no one has ever come out of a psychedelic trial for depression feeling more depressed (listen to this interview, 7 mins 30 seconds in: ‘no one’s ever come out more depressed). He says the risks of psychedelics have been ‘grossly, grossly exaggerated and the benefits deliberately minimized’.

Nutt’s authority and positive views on psychedelic risk were sufficient to sway the mind of a shadowy figure known as ‘the delegate’, who apparently wields huge power over the TGA, Australia’s equivalent of the FDA. After Nutt’s presentation, ‘the delegate’ changed the TGA’s decision of the previous year, and gave approval for psilocybin and MDMA to be used as psychiatric treatments for treatment-resistant depression and PTSD, much to the surprise of everyone in Australian healthcare.

Some drug experts have since questioned Nutt’s assessment of psychedelic risk. Professor Anna Lembke is Chief of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic at Stanford University and the author of Drug Dealer, MD: How Doctors Were Duped, Patients Got Hooked, and Why It’s So Hard to Stop. She says: The truth about drugs

I’ve seen his study cited and presented numerous times as evidence of the relative safety of “LSD” and “Mushrooms” and by inference other psychedelics/hallucinogens, when in fact it does not represent real evidence. First of all, these data are not based on objective findings such as emergency room visits, hospitalization, coroner’s report, or any other standard epidemiologic approach for assessing population harms. From what I can gather from reading the article, these quantitative comparisons are based on a group of individuals sitting around a table reporting their own thoughts about the safety of different substances, based on, well, their own thoughts. The graph also fails to account for is the prevalence of drug use in the population. When drugs are readily available and commonly used in a population, like alcohol, they cause more harm than drugs that are hard to access and less commonly used. The rankings in this graph do not account for prevalence of use.

In other words, Lembke says the risk scores of the drugs in Nutt’s graph were simply decided by Nutt and other members of Drug Science back in 2010, before there had been any systematic studies of psychedelic risks. It’s also markedly different from a list Nutt and colleagues produced three years earlier, in which heroin was rated the most harmful drug, alcohol was fifth and LSD was mid-table. How did alcohol become so much riskier in three years?

Alcohol advocates, meanwhile, say it’s not true that Drug Science presents ‘the truth about drugs…free from commercial influence’ and point out that Nutt has been developing a commercial alternative to alcohol for 15 years, ever since he published the 2010 table, so he has a financial incentive to emphasize the harm of alcohol.

He’s also on the supervisory board of several psychedelic companies, such as Mega psychedelic shop, Awakn, Psyched Wellness and Algernon Pharmaceuticals, and his Australia trip was funded by Mind Medicine, the Australian company set to profit from the TGA’s decision to legalize psychedelic therapy (he’s also on the faculty for its new psychedelic therapy course). So, according to critics, it is misleading for Drug Science to present itself as ‘free from commercial influence’. On the contrary, the scientists involved stand to make a fortune from our changing drugs landscape. I don’t have any problem with scientists making money from their research — but let’s be honest about our potential conflicts of interest when we’re talking about risks. The truth about drugs

It’s also not true to say no one came out of any psychedelics-for-depression trials feeling more depressed. In Compass’ big 2022 trial of psilocybin for depression, more serious adverse events — specifically, suicidality — occurred among the psilocybin groups than the control group. In Imperial’s own trials, some participants did initially feel more depressed, before improving. In other trials, we don’t know how individual patients fared as we’re only presented with the average result for the group.

Nor is it the case than no one has ever had a psychotic reaction in a clinical trial, and therefore psychedelics are totally safe in clinical settings. Of the 769 people who have gone through psychedelic RCTs in the last 15 years, I personally know one person who was put on anti-psychotics after taking part in a trial, and another who reported feeling psychotic after taking part in MAPS’ trial for MDMA. Neither of these incidents appeared in the trials write–ups — we heard about them when the participants spoke or wrote about their experience independently.

Leave a Reply